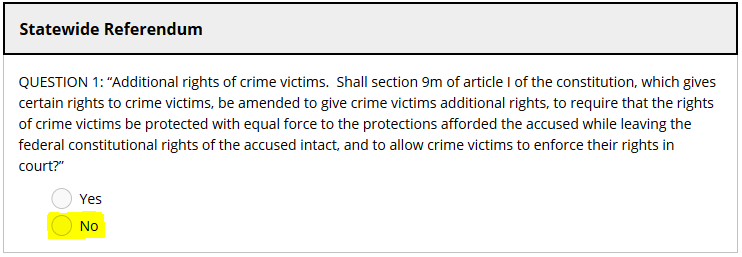

The April 7th election is almost here, and you may have already received your absentee ballot. This year there is a special referendum question on whether or not you would like to see a change in the state constitution relating to victims’ rights, otherwise known as Marsy’s Law.

We at End Abuse acknowledge that there is a spectrum of stances on the topic of a victims’ rights amendment, and we understand that some of our member programs may differ in opinion. As we endeavor to center the last survivor in our work, End Abuse has decided to oppose Marsy’s Law. This is a departure from our initial position of remaining neutral, and we feel it is important to provide our reasoning. We appreciate you for taking the time to learn, and thank all victim advocates for the important work you do every day.

What is Marsy’s Law?

Marsy’s Law is an amendment to the constitution. The amendment largely duplicates existing victim protections, but goes further in several areas: victims would have the right to be heard at plea, parole, and revocation proceedings; the right to refuse defense attorneys’ interviews, deposition, or discovery requests; and the right to attend all proceedings in their cases.

Victims’ rights and defendants’ rights

Victims’ rights are not rights against the state. Instead, they are rights against another individual.

The U.S. Constitution and the constitutions of all 50 states guarantee defendants’ rights because they are rights against the state, not because they are valued more by society than victims’ rights. Defendants’ rights only apply when the state is attempting to deprive the accused – not the victim – of life, liberty, or property. They serve as essential checks against government abuse, preventing the government from arresting and imprisoning anyone, for any reason, at any time.

However, the Marsy’s Law formula includes the rights to restitution, to reasonable protection, and to refuse depositions and discovery requests, all of which are enforced against the defendant. Such rights do nothing to check the power of the government. In fact, many of the provisions in Marsy’s Law could strengthen the state’s hand against a defendant, undermining a bedrock principle of our legal system — the presumption of innocence.

Wisconsin already has clearly defined victims’ rights both in statute and in the current constitution. We are concerned about the potential of the amendment to further confuse a criminal justice system which is already overburdened and underfunded.

Why is this harmful for the last survivor***?

***When we refer to the “Last Survivor,” we build off a concept introduced by Jackie Payne of Move to End Violence surrounding the Last Girl. We mean advocating for community supports that address the needs of the most marginalized community member, or the Last Survivor. Centering the realities and needs of these marginalized groups in turn enables us to reach all survivors and create effective, sustainable movement toward ending domestic violence and other forms of oppression.

The apparent contradiction between the stated goals of Marsy’s Law and End Abuse’s opposition can be explained in several ways.

-

- While we traditionally think of victims and defendants as existing totally separate from one another, in reality, the lines between them are often murky. The two categories may seem diametrically opposed, but numerous survivors of domestic violence across the state will find themselves sitting in court both as victims and defendants over the course of their journey to safety and empowerment. Victim arrests occur in cases of self-defense or when charged with violating their own protective orders for allowing an abusive partner into the house because they could not keep him from being disruptive outside and feared eviction. When both parties are arrested, victims often plead guilty so they can return more quickly to children or a job. Women comprise a larger proportion of the prison population than ever, and most are survivors of violence.

- Crime victims and the accused share a common interest in making the system more transparent and accountable. Communities that suffer most from violent crime are often the ones that bear the brunt of mass incarceration and police violence. Wisconsin has some of the most racially disparate criminal justice outcomes in the nation. The presumption of innocence is already not a reality experienced by domestic and sexual violence victims, especially those from marginalized communities. Routinely, biases based on race, gender, or immigration status result in the arrest of victims seeking assistance.

- Without a serious commitment to large increases in funding for various aspects of the criminal justice system, many of the requirements in this proposal could result in an increased strain on the court system. As we have now seen in other states that have passed Marsy’s Law, this is likely to result in new administrative burdens and longer delays for trials as the system attempts to comply with new constitutional provisions, an issue that already plagues victims of crime in Wisconsin today.

- Legislation that trades expanded victims’ rights for potential limits on due process could result in a wide array of problems, including negative consequences for survivors.

- Pitting victims’ rights against defendants’ rights means that defendants’ rights may lose in certain circumstances. Defendants’ rights against the state will be weakened or unenforced in some cases, potentially at a significant cost to constitutional due process. In other words, the chances that an innocent person could be convicted of a crime they did not commit could potentially increase. The proponents of Marsy’s Law may not intend for this outcome, but nothing in their formula prevents it.

With these considerations in mind, reforming the criminal justice system does not necessarily mean simply leveling the playing field between victim and accused, but rather making the entire process trauma-informed, training the court’s representatives to better understand the experience of survivors, and ensuring that currently existing resources are adequately funded to better serve victims.

The assertion that victims of crime need rights of equal weight to those of the accused is a mischaracterization of how the American criminal justice system functions. Any legislation that trades expanded victim’s rights for potential limits on due process could result in a wide array of problems that are as of now unforeseen.

The focus on assisting victims is commendable, but what we hear most often from victims and advocates is not that they wish the constitution would be amended, but rather that they are in dire need of a more holistic approach to criminal justice. Victims and advocates talk frequently about lack of access to legal aid, underfunding of county victim witness units, chronically overworked and underpaid DAs and public defenders, restrictions on access to Medicaid and other lifesaving benefits, sparse or nonexistent affordable housing in their area, and insufficient focus on interpersonal violence in our education system. Policies addressing these issues are the policies Wisconsin survivors need.

Opposing Marsy’s Law does not mean we oppose victims’ rights; it means we support the empowerment of victims in a different way. We recognize that due process is a fundamental right that in many ways serves as the foundation of the criminal justice system. We will continue to center all victims of violence in everything that we do.

If you have any questions or concerns, please don’t hesitate to reach out to End Abuse Director of Public Policy:

Jenna Gormal

Pronouns: she, her, hers

Office: (608) 255-0539, Ext. 361 | Direct: (608) 237-3985